What can software developers really learn from SpaceX Raptor 3 engine?

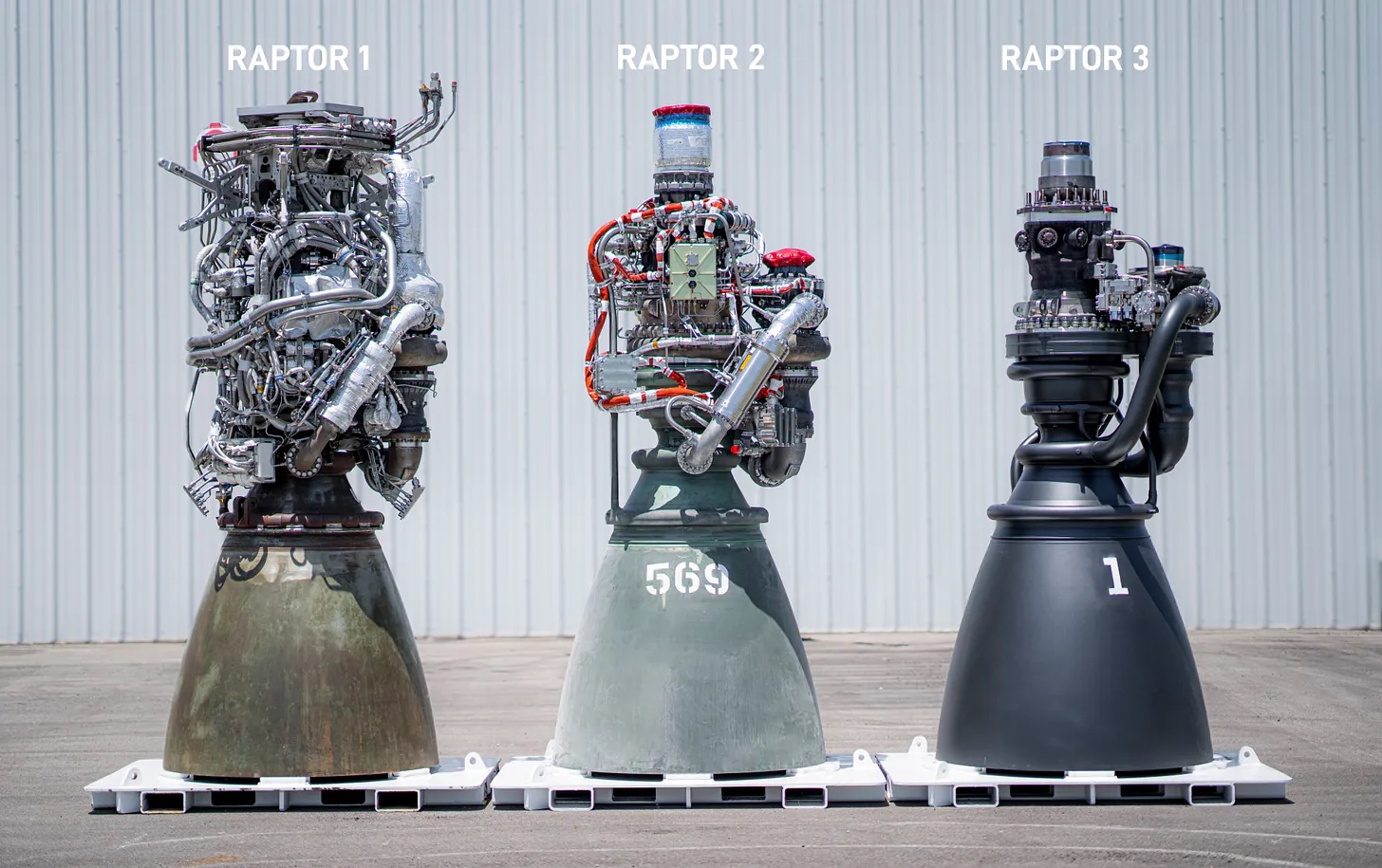

On August 3rd, SpaceX revealed the Raptor 3 engine which looks stunning: They have achieved a very impressive sleek and simplified design while greatly increasing the specs. The difference is even more striking when seen compared to its previous iterations:

Very soon there were Twitter/X/Linkedin posts with analogies to software engineering, mainly using one of the press images to make a comment about needless complexity in software engineering. For example, suggesting a popular framework is developing like Raptor, but in reverse, adding complexity. Or saying that any framework is Raptor 1, and Raptor 3 is developing from scratch without using a framework. I see the points they’re trying to make but, with few exceptions, I don’t see how they’re related to Raptor engine development at all. Let’s be honest: as an industry, we sometimes torture analogies beyond the point of decency.

But, I like a good analogy as much as the next software developer. With software having no physical form, we often resort to analogies in the physical space. And engines of all forms are often a great fit. This one can be used well. In an attempt to do it proper justice I read up on what little information is available on how Raptor 3 was developed to extract some well grounded lessons for software engineering.

I am a mathematical engineer by education and software engineer by profession. This means I am woefully under-qualified to really understand rocket engines. If you are qualified and notice I am off in my interpretation of Raptor 3 development please let me know. I will be grateful for the correction.

The value of iterative development

The simplified and streamlined design of Raptor 3 is a result of Space X applying everything they learned on previous 2 versions. It’s not a result of them making mistakes and then correcting them. In other words, Raptors 1 and 2 were necessary steps towards 3. Trying to jump to 3 would not have worked, they would not have the knowledge needed to know:

- What can be removed.

- What needs to stay the same.

- And how the rest can be simplified and improved at the same time.

In software we have an unrivalled ability to iterate, second to no other engineering discipline. We should embrace this. There is no need to birth a final design on the first try. In fact, that is perhaps the best way to create a mediocre or bloated design.

Instead, embrace iterations and be comfortable temporarily increasing complexity as long as it leads to learning. This learning is what will enable iterating to the better design.

Best part is no part

“Best part is no part” Elon Musk

The best way to reduce complexity is by removing. Most striking in Raptor 3 appearance is how many fewer parts it has.

This analogy translates directly to software. Can you reduce code while maintaining functionality? Can you remove a part of infrastructure? Can you eliminate a subsystem, class, function, entirely? All of these are wins.

Be extra proud of commits with negative line count diffs.

Invest in your tooling

A big factor in enabling all of the Raptor 3 simplifications is SpaceX investing in additive manufacturing. Elon Musk went as far as claiming SpaceX has the most advanced metal 3d printing technology in the world.

Ok, sure, with physical engineering it’s obvious that you need tools to produce it. With software, theoretically you just need a keyboard. And we can go very far by just using open source or off the shelf tools. And that’s part of the problem. It’s all too easy for companies to decide they “don’t have time to invest in tooling”. Sometimes that’s the right decision but for too many companies it becomes the only acceptable decision.

Yet, modern software development tools greatly enable productivity. Why are companies so hesitant to invest in custom tooling to solve custom needs?

Most companies would benefit from investing more in own tooling to enable more internal innovation.

Try solutions outside the norm

Raptor 3 departs from other rocket engines in many ways, resulting in significant improvements.

This one is tricky. As software developers we are prone to reinventing the wheel when we should stick to the tried and true solutions. However, we also cling onto known good solutions long enough to miss creating a great solution.

Start by understanding your current solutions. This is hard, sometimes very hard. However, if you do that you will have the authority to conclude that the existing solutions are not a good fit for your problem. Then don’t hesitate to go wild and experiment outside the common wisdom. If you’ve already applied the other lessons, you’ll be in a strong position to pull it off.

Perhaps you might just develop the next software equivalent of Raptor 3 rocket engine.