Exercise: Minesweeper in 100 lines of clean Ruby

This article is part 1. Part 2 uses code from this article to make the game multiplayer using Rails and Hotwire.

Ruby is such an expressive language. You can often do surprisingly much with just a few lines of code. It’s why I find it so satisfying to think about how to accomplish the same thing in fewer lines of Ruby1.

I want to be clear: I am not talking about Code Golfing, although that can also be fun. I’m talking about reducing the number of lines of code without loosing the readability. In fact, one of the nicest things about Ruby is how often reducing the number of lines of code can increase readability.

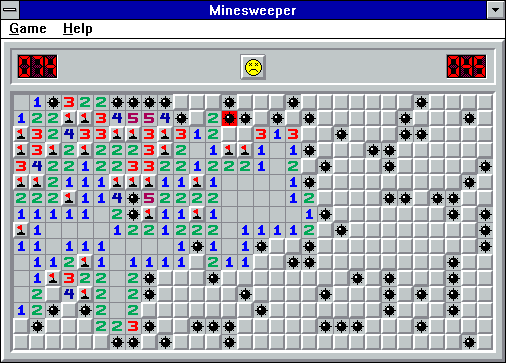

As an exercise, let’s do this with good old minesweeper. I remember playing it on Windows XP when I was a kid. If you also have such memories, well, hello fellow millenial!

For practice, I implemented it in CLI form in vanilla Ruby. Get my fully implemented version here. If you want to do it yourself, stop here and come back later to compare. The rest of the article walks through my implementation which landed on exactly 100 lines (counted by cloc in lib folder) by a happy accident. No, really, I didn’t cheat to make it be a round number. I was planning on doing it but turns out I didn’t have to.

Along the way we’ll also refresh our memory of some less often used Ruby features. I can’t learn new things in a vacuum. I prefer to learn in context of a mini project over learning from Changelog overviews.

Generating the playing board

The first thing we need is a Board class to represent, drum roll, the board. The board is fully defined by its width, height and the locations of mines:

1

2

3

class Board < Data.define(:width, :height, :mines)

# content ...

end

Here we’re using a feature introduced in Ruby 3.2, Data class. It’s perfect for defining immutable value objects. If you’ve used if before you’re probably wondering why I didn’t use the usual syntax of Board = Data.define(...) do ... end and instead inherited from it. That will be explained a bit later.

We’ll create the board by randomly placing a number of mines on it. We can’t just give each mine a random pair of coordinates because then we could end up with 2 mines in the same location. Instead we want to take all possible locations on the board and then randomly take some of these locations.

Thankfully, in Ruby this is not far from the plain English description:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

class Board < Data.define(:width, :height, :mines)

# ...

def self.generate_random(width, height, mines_count)

full_board = Enumerator.product(width.times, height.times)

.map { |x, y| Coordinate.new(x, y) }

self.new(width, height, full_board.sample(mines_count))

end

# ...

end

The product enumerator takes two enumerators and returns their cartesian product. That’s a mathematical way of saying: “every element from first list, combined with every element from second list”. This effectively gives us all of the possible coordinates. And then we call sample which takes a number of random elements from a collection. I could have inlined that call to save lines but I felt like using full_board variable has a nice self documenting effect.

The Coordinate class starts as another simple Data object:

1

Coordinate = Data.define(:x, :y)

The Board should also determine if a specific cell has a mine or is empty. If it is empty we want to know how many neighbouring mines it has. Since mines is already just an array of Coordinate objects, we can use it directly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

class Board < Data.define(:width, :height, :mines)

# ...

class Mine; end;

Empty = Data.define(:neighbour_mines)

def cell(coordinate)

mines.include?(coordinate) ? Mine.new : Empty.new(count_neighbours(coordinate))

end

private

def count_neighbours(coordinate)

mines.count { |mine| mine.neighbour?(coordinate) }

end

end

The Mine and Empty nested subclasses are why here I inherited from Data defined class, they’ll be needed outside this context. They would not be visible from inside a Data.define do; end block.

Yes, the method that counts the neighbours is not optimal as it checks all mines. For now, let’s keep the very readable simple version and optimise if needed.

In that last method, a mine is just a coordinate and we use a neighbour? method we haven’t yet defined. We define it by checking that the distance in either coordinate is less than or equal to 1:

1

2

3

4

5

Coordinate = Data.define(:x, :y) do

def neighbour?(other)

[(self.x - other.x).abs, (self.y - other.y).abs].max <= 1

end

end

With that we’ve finished the Board class.

Playing the game

We’ll leave the actual playing of the game to a new class named, shockingly, Game. It needs: an instance of the board object and a map of what has been revealed so far:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Game

def initialize(board)

@cells = Array.new(board.height * board.width, nil)

@board = board

end

# ...

end

Initially nothing has been revealed so we initialise an array matching the board size. By default it’s initialised with all nil.

We’ll reduce the interface to a single reveal method which is what we’ll run when we “click” on a cell to reveal it. The only tricky part is that when you reveal a cell that has no neighbouring mines, the game should then recursively auto reveal all neighbouring cells. This is what causes the satisfying “pop” when a whole area becomes revealed at once. We’ll implement the logic just as we described it now, by recursively revealing all neighbouring cells:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

class Game

# ...

CELL_WITH_NO_ADJACENT_MINES = Board::Empty.new(0)

def reveal(coordinate)

index = cell_index(coordinate)

return :play if @cells[index]

(@cells[index] = @board.cell(coordinate)).tap do |cell|

return :lose if cell.is_a?(Board::Mine)

reveal_neighbours(coordinate) if cell == CELL_WITH_NO_ADJACENT_MINES

end

@cells.count(&:nil?) == @board.mines.size ? :win : :play

end

private

def cell_index(coordinate)= coordinate.y * @board.width + coordinate.x

def reveal_neighbours(coordinate)

coordinate.neighbours(width, height).each { |n| reveal(n) }

end

end

This effectively performs a Breadth-first search of the board when a cell-with-no-adjacent-mines is revealed. There are 2 key parts making it work:

- The early exit from the method when a cell has already been revealed.

- Assigning the revealed value before recursing into calling reveal on the neighbours. This prevents hitting infinite recursion when a neighbour we just revealed tries to then reveal the original cell.

Finally, if we hit a mine we exit early with :lose. Otherwise we check if all the remaining cells are just mines and, if yes, return :win. All other cases return :play.

The only thing missing here is the neighbours method on the coordinate. We implement it by first creating a list of offsets to all 8 neighbours:

1

2

3

4

Coordinate = Data.define(:x, :y) do

NEIGHBOURS = (Enumerator.product([-1, 0, 1], [-1, 0, 1]).to_a - [[0, 0]]).map { |x, y| self.new(x, y) }

# ...

end

We’re again using product except this will also include the centre which we remove by subtracting [0, 0] from the list.

The list of actual neighbour coordinates is then formed by adding all neighbour offsets to the coordinate and removing any that fall outside the board:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Coordinate = Data.define(:x, :y) do

# ...

def +(other)

self.class.new(self.x + other.x, self.y + other.y)

end

def neighbours(board_width, board_height)

NEIGHBOURS

.map { |n| self + n }

.reject { |n| n.x < 0 || n.x >= board_width || n.y < 0 || n.y >= board_height }

end

end

ASCII printing the board

To print the board on the command line we’ll iterate over the grid, converting the cells to ASCII characters:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

AsciiRenderer = Data.define(:grid) do

def render(output = $stdout)

grid.height.times do |y|

grid.width.times do |x|

output.print case cell = grid.cell(Coordinate.new(x, y))

when nil then "#"

when Board::Mine then "*"

else cell.neighbour_mines.zero? ? "_" : cell.neighbour_mines

end

end

output.puts

end

end

end

This will print something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

___1#1_______1#1___1#1__1#1___

___111_______111___1#1__1#1___

11_________________111__1#211_

#21111_______111111_____1###1_

#####1_______1####311___12#21_

###211__111__111####1____111__

###1____2#2____1#2211_______11

###1____2#2____1#1__________1#

Notice that it expects width, height and cell methods which we have defined on Board but not onGame and we actually need to print instances of Game. Let’s define them:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Game

# ...

def width = @board.width

def height = @board.height

def cell(coordinate) = @cells[cell_index(coordinate)]

# ...

end

Here we’re using endless methods. Yes, they did save 2 lines per each method, playing a role in the full game being exactly 100 lines, but that’s not why I used them! The only requirement of endless methods is that the method body is just one expression, how ever many lines it spans. Notice there are several methods on Coordinate and Board which could also be endless methods. I didn’t use it there because the result wasn’t very readable. Aesthetics matter.

Putting it all together

Finally, we assemble all components into a playable command-line game.

We want to be able to run it with ruby lib/play.rb 20, 10, 20 and params defining: width, height, and number of mines. For that we’ll parse the command line arguments:

1

2

3

4

5

if ARGV.size == 3

Minesweeper.play(*ARGV.map(&:to_i))

else

puts "Usage: ruby lib/play.rb width, height, mines_count (e.g. 'play.rb 12 6 6')"

end

And now we just define the play method as a module function. We’ll use Readline module to print a prompt and read one line at a time. It’s the same thing used under the hood by IRB. :

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

module Minesweeper

module_function def play(...)

game = Game.new(Board.generate_random(...))

renderer = AsciiRenderer.new(game)

renderer.render

while input = Readline.readline("Type click coordinate as 'x, y' (0 based)> ")

result = game.reveal(Coordinate.new(*input.split(",").map(&:to_i)))

renderer.render

if [:win, :lose].include?(result)

puts "You #{result == :win ? "win" : "lose"}!"

return

end

end

end

end

Notice that we’re using here def play(...) . That syntax was added in Ruby 2.7. to support uses cases where all parameters are simply forwarded. Here, the parameters need to be completely forwarded to Board.generate_random and then we add gameplay logic around it.

What next?

You can get my fully implemented version here. If you’ve implemented your version for practice, please share it in the comments.

Now, this is technically a fully playable minesweeper implementation but it’s not exactly fun to play. CLI is not a great fit for Minesweeper. That’s why in the next post we’ll package it into a Rails + Hotwire application. And just for fun we’ll make it multiplayer, because why not. Stay tuned.

If we accept the claim that that number of bugs correlates with number of lines of code this is not just a fun exercise. There’s real business value in accomplishing a feature with less lines of code. ↩