Exercise: Multiplayer Minesweeper with Rails and Hotwire

In the last blog post I implemented Minesweeper as a CLI game, in just 100 lines of clean, readable ruby. That was a fun exercise. But CLI is not a great UI for minesweeper. So let’s package it into a Rails app! And, let’s also make it multiplayer!

“But, Radan”, I hear you say: “this doesn’t make sense, Minesweeper is a single player game”. Ok, that’s true, but you could have multiple people clicking on the same board. Aaand, it could be totally open so anyone can play … aaaand there’s just one ongoing game, when it finishes a new one starts right away … aaand we keep a score of how many games humans won and how many mines won1. “This sounds really stupid” you might say and you are probably right. But, I’ll still do it.

I won’t be going into the details of every aspect of the implementation. Most of it is straightforward Rails. I will focus on the key parts that make the multiplayer work. That is the interesting part.

What makes multiplayer hard?

To make it multiplayer we need to:

- Allow concurrent play. This is relatively easy. We will build a simple web UI with Rails and making it concurrent just means allowing everyone to click on the same minesweeper board.

- Make the board update in real time. This is where Hotwire will come in. For a game like minesweeper the standard ActionCable powered broadcast updates will be enough.

- Make the game resilient to race conditions during parallel play. This is the trickiest part. We have to assume that players will be clicking on the board at the same time. The game must handle it so that no matter how players play, they always see a valid and up to date state of the board. In other words it has to be free of race conditions.

The last point is the most complex one and we’ll start there. The key part that will simplify this part is the choice of the data model. So let’s start there!

The data model

If you read the previous post you might remember that we had 2 main, pure Ruby classes:

Minesweeper::Boardwhich contains a list of mines defined by their coordinates and can return information on a cell: if it has a mine or, if it not, the number of neighbouring mines.Minesweeper::Gamewhich holds the state of what was currently revealed, tracks win/lose status and exposes a singlerevealmethod which is what we call when we “reveal” a cell on the board.

The data model will closely follow that setup with addition of the Click model. Click record holds the coordinates of a cell we clicked on, i.e. revealed.

In other words, this is the full Entity-Relationship diagram:

erDiagram

Board ||--o{ Mine : contains

Board {

width integer

height integer

}

Mine {

x integer

y integer

}

Game ||--o{ Click : has

Game {

state enum

}

Click {

x integer

y integer

}

Game ||--|| Board : "is played on"

How does this data model make multiplayer easier?

Notice that we’re not storing the current state of the game anywhere in the database. Instead, whenever we need the current state of the game we’ll recreate it by:

- Loading the Board’s mine locations from the database and initialising

Minesweeper::Boardwith them. - Initialising a new

Minesweeper::Gameobject with it. - Replaying the game by calling

revealmethod with coordinates from click records, ordered by the auto-incrementingidcolumn.

That last part is crucial. When we receive parallel clicks from multiple players we need a robust way to decide what is the actual order in which they should be applied. With that last part we’re outsourcing that to the database. In other words, the database2, as the source of truth, is resolving the order of clicks by assigning them ids. Whoever manages to write the click to the database first is counted as the first click. This ensures that all players see a consistent state and that however fast they click the end result is the same as if they all patiently waited their turn to play.3

Since the state of the board is recreated by replaying the clicks, we don’t need to store it. By omitting it, we are keeping the database in a high normal form. In general, high database normal forms can eliminate most of the race conditions at the database level.

Recreating the current game state from the database

The only thing we need to do is to ensure that when we render a state of the game we are doing it with all of the clicks saved to the database up to a specific id. It’s possible that while we are rendering a new click will arrive but that’s not a problem for us. We’ll be rendering an old state but it will still be a valid old state. The only important thing is to make sure that we don’t skip clicks lower in the sequence because that could lead to us rendering a completely invalid state.

That is ensured by having the method that generates the game object always go back to the database for the most up to date list of clicks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def to_game_object

Minesweeper::Game.new(board.to_game_object).tap do |game|

clicks.ordered.pluck(:x, :y).each do |(x, y)|

game.reveal(Minesweeper::Coordinate.new(x, y))

end

end

end

That ordered scope is ordered by id: scope :ordered, -> { order(:id) }

Hotwire and Rails setup

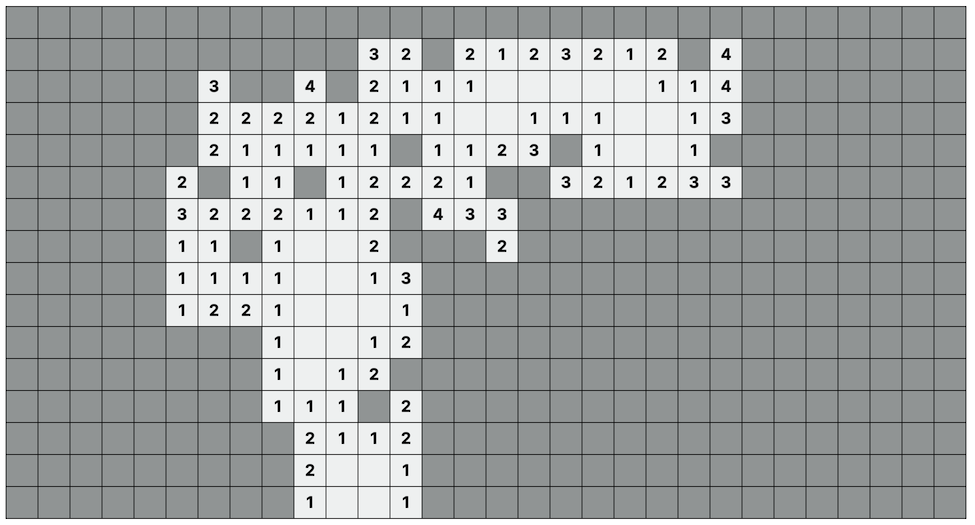

To render the board I chose a table element since it is the simplest but there are better ways to do it. I iterate through the cells and render each row of the minesweeper board as a table row and each board cell as a table cell. Hidden cells are shaded and revealed cells have the number of neighbour mines rendered on them. The end result is a simple but clear minesweeper board:

Let’s talk about how we can make it interactive.

Just rely on Turbo Drive

Not the fastest but very simple way is to do nothing fancy and let Turbo Drive do what it can.

- Every empty cell is a link tag which uses

data-turbo-method=postto make it a post submission. - Clicking the empty cell submits a POST request that creates a click record and redirects back to the same page.

- Turbo Drive detects it’s a redirect back to the same page and refreshes it. We enable Turbo Morphing to get nicer updates.

For that we need just two endpoints:

1

2

3

4

# Home page which is also the game page and renders the board

root "games#home"

# The update endpoint which processes the clicks.

post "games/:id/:x/:y", to: "games#update", as: :reveal

Make it more efficient with a turbo frame around the board

The pure Turbo Drive setup means we have to make two round trips to the server on each click. In such a fast paced game like minesweeper that is unacceptable! Let’s reduce this to the one round trip and have the update action return the fresh board.

The change is simple, first we will wrap the board rendering in a turbo frame:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

<%= turbo_frame_tag game do %>

...

<table>

<% board = game.to_game_object unless local_assigns.key?(:board) %>

<% board.height.times do |y| %>

<tr>

<% board.width.times do |x| %>

... rendering the cell ...

<% end %>

</tr>

<% end %>

</table>

<% end %>

Rails takes care of the rest and the hidden cell links are now updating the turbo frame directly. We can render the above partial when responding from update action:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def update

x, y = params.require([:x, :y])

game = Game.find(params[:id])

game_object = game.reveal!(x:, y:)

render partial: 'games/game', locals: { game: game, board: game_object }

end

Notice that, in order to determine if we have won or lost the game, the update action must already calculate the new state of the game object. To do that it has to:

- Store the new click.

- Replay all of the clicks so far. It relies on the

Game#to_game_objectmethod explained above to do this with an up to date list of the clicks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

class Game

#...

def reveal!(x:, y:)

clicks.create!(x:, y:)

to_game_object.tap do |new_game_object|

update!(status: new_game_object.status)

end

end

end

Since it already has to do all that, rendering the board right away is pretty cheap, it is reusing the just calculated game object.

Updating other players

With Hotwire it’s very simple to make it a multiplayer game, especially with our super simple setup of: there is just one game and everyone can play it. See, that wasn’t so crazy!

In the Game model we add broadcasts_refreshes and then in the view we add:

1

<%= turbo_stream_from @game %>

And when we click … nothing happens.

Our clever setup means that clicking just creates a new click record, i.e. there’s no change on the associated game record so no refreshes will be broadcast. However, if we modify the association on Click model to:

1

belongs_to :game, touch: true

This means that every new click record we create will automatically update the updated_at column on the Game record, triggering a refresh broadcast. And just like that, the game is now multiplayer.

Why broadcasting just a refresh is important for multiplayer

It’s very important that we don’t broadcast the new state of the game, but instead broadcast a refresh turbo stream action. It doesn’t carry data, but simply instructs the browser to refresh the page. This means that we don’t have to care about updates from other players coming in the correct order. If refresh actions come out of order we will still fetch the most up to date game state from the server.

Making it efficient with caching

Our data model is great for resolving race conditions but it’s not very efficient. Whenever we need the current state of the game we have to replay all of the Click records. We now resolve that in the view layer by caching the board rendering:

1

2

3

4

5

<% cache model do %>

<%= turbo_frame_tag model do %>

...

<% end %>

<% end %>

Since Rails by default uses updated_at as part of the cache key, the same touch mechanism we set up for refresh broadcasting also ensures that the cache is busted when needed. And with multiplayer minesweeper being read heavy we’ve now eliminated most of the performance issues of the application.

What next?

The game is live and can be played at minesvshumanity.com. Yes, I got the domain for it, because why not. Please go play it!

The full code of the application is public and the repository is here.

A good way to verify if code architecture is good is to pay attention to how easy it is to add a new feature. And we’re still missing the ability to flag locations where we think there are mines. This is essential to improving the playability of Minesweeper!

If you want to practice, I invite you to try and add the feature yourself. I’ve tagged the version that matches everything explained in this article. You can check it out and try adding mine flagging yourself.

If you just want to see how I did it, here is the commit where I’m adding it to the main branch.

Footnotes

Mines win by humans losing, because mines are not intelligent, just artificial, see what I did there, wink, wink … I’ll see myself out. ↩

In this case I’m using SQLite3 but the basic mechanism is so basic that it would work with any SQL database. ↩

In the previous article we already coded the game logic to ignore double clicks. Multiple clicks on the same cell can still be stored and they are resolved by the game logic. ↩